Rowing has never been a neutral sport.

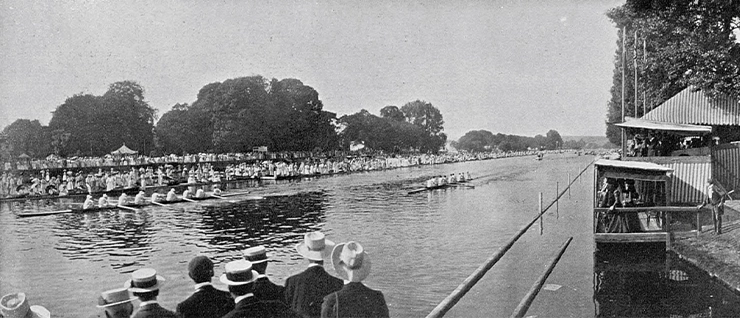

For much of its history, it was shaped by rules that quietly, and sometimes explicitly, determined who belonged and who did not. Few events reflect that more clearly than the Henley Royal Regatta

From its early days, Henley enforced strict definitions of amateurism that excluded anyone who earned money through sport or manual labour. Coaches, watermen, tradesmen, and even policemen were deemed unsuitable. These rules were not about fairness on the water, they were about preserving a particular class of competitor. One notable example came in 1936, when the Australian National Eight was excluded because one crew member was a policeman, a profession classified at the time as a trade..

Those rules are long gone, but the legacy of exclusion lingered, particularly for women.

For decades, Henley Royal Regatta was simply out of reach for club women.

In the 1980s, rather than restructuring Henley to meaningfully include women, it was suggested that women organise their own regatta. From that decision, Henley Women's Regatta was born. Through persistence and determination, particularly from event organisers Rosie Mayglothling and Christine Aistrop, the first regatta was held in 1988.

Viewed through a contemporary lens, it is clear the regatta faced significant obstacles. The Henley Royal Regatta enclosures and tents were off-limits, requiring the course to be reimagined. When participation grew to the point of needing a second day of racing, permission was initially denied due to existing men's traditions.

While women were navigating these challenges, Henley Women's Regatta persevered. Its history shows not only the barriers women faced, but also their ingenuity, resilience, and dedication to creating competitive opportunities that did not previously exist.

Attitudes have shifted significantly since the 1980s. Beginning in 2012, Henley has steadily introduced women's events into the regatta. Fourteen have been added to date, and in 2026, three new intermediate and club women's quad events will provide global opportunities that simply did not exist before.

What matters most is how this parity is being achieved. By 2027, Henley expects to offer an equal number of men's and women's events. Achieving this balance requires suspending some long-standing men's events, a structural decision that prioritizes equity and progress over comfort and tradition.

For a regatta so defined by its history, that choice carries real weight and is something to celebrate.

Henley is not acting in isolation. Across the sport, rowing's governing bodies are beginning to address gender equity not just in competition, but in leadership and coaching, the spaces where culture is shaped.

At the 2025 International Federation Forum, World Rowing presented its long-term work on advancing gender equality in coaching. This effort, ongoing for more than a decade, combines embedding gender equity across development pathways with targeted programs to support, educate, and retain women in coaching roles.

At junior and learn-to-row levels, women are highly visible and widely welcomed. These environments often have strong female communities and provide valuable opportunities for young women to gain experience, confidence, and income while continuing their studies.

As coaches progress to higher levels, representation becomes less consistent. While coaches such as Paralympic gold-medallist Christine McClaren and Australian national-level coach Ellen Randle show that progression is possible, women remain underrepresented in elite coaching pathways.

Equity at this level is not simply about representation. When women are visible as coaches and leaders, athletes are far more likely to imagine a future for themselves in the sport beyond their competitive careers. Initiatives like those led by World Rowing are important steps forward, and real progress depends on embracing them and reshaping the cultures that influence opportunity.

Equity on the water matters, but so too does equity off it.

Another major shift in rowing reflects the challenge of making the sport more equitable, accessible, and sustainable in the modern era.

For decades, lightweight rowing provided one of the sport's most important inclusion pathways. Introduced to the Olympic programme in 1996, lightweight events allowed smaller athletes, men and women who did not fit the typical open-weight physique, to compete at the highest level. For many, it was not a compromise, it was the reason they belonged in the sport at all.

After the Paris 2024 Olympic Games, lightweight rowing will no longer be part of the Olympic programme. This change has meaningful consequences for athletes and club communities. While some lightweight rowers can adapt to open-weight competition, others will lose their primary pathway to national representation and may pursue other sports where high-performance opportunities remain.

At the same time, rowing is expanding in a new direction. Coastal rowing, particularly beach sprints, will debut as an Olympic discipline in Los Angeles in 2028. This format requires less infrastructure, operates in open-water environments, and brings the sport to coastal communities where flatwater rowing has been less accessible.

From an equity perspective, this evolution is significant. Coastal rowing challenges assumptions about who rowing is for and what an elite pathway can look like. It opens doors to athletes from regions without major facilities and invites diverse body types, skills, and backgrounds into the competitive landscape.

The loss of lightweight rowing is real, but considered alongside the emergence of coastal rowing, the expansion of women's events at Henley, and World Rowing's investment in gender equity in coaching, it also signals a broader willingness to reshape the sport even when that reshaping is challenging.

Rowing beyond school in Australia is challenging. Many athletes fall in love with the sport in a thriving school environment, where structured coaching, access to equipment, and a strong sense of community help them develop skills and identity within the sport.

That sense of camaraderie is on full display each March at the Head of the Schoolgirls' Regatta in Victoria. The largest regatta in the Southern Hemisphere, it brings together thousands of school-aged athletes from private schools, public schools, and some clubs. Its power lies not only in elite performance, but in inclusion, as athletes of varying ability levels have meaningful opportunities to race throughout their school careers.

After school, that pathway narrows. Club rowing for women in Australia struggles not for lack of talent or interest, but because there has been little to aspire to between school and masters rowing. While each state offers club racing, and the Australian Rowing Championships includes three lub-level events for women, with athletes limited to entering one due to scheduling, these opportunities alone have not been enough to sustain participation through early adulthood.

AThe introduction of intermediate and club women's events at Henley has the potential to change that equation. With two new club events and an intermediate category, women are offered something tangible to aspire to, a reason to commit to training, testing, selection, and racing after school. Additionally, the growth of coastal rowing, particularly beach sprints, provides an accessible and exciting avenue for women to remain engaged in competitive club rowing even in regions without traditional flatwater facilities. Together, these developments create pathways that help ensure rowing does not have to end when school does.

For a sport once defined by exclusion, rowing is beginning to show what genuine leadership looks like.

Henley Royal Regatta demonstrates that tradition can evolve even when evolution requires sacrifice. World Rowing's work in advancing gender equity in coaching shows that inclusion must extend beyond start lines and finish posts into the structures that shape opportunity. And the emergence of new disciplines like coastal rowing highlights a sport willing to meet athletes where they are rather than insisting they conform to outdated models.

Together, these shifts send a clear message to women everywhere: you belong here, as athletes, as coaches, and as leaders.

This is not the end of the story. It is the beginning of a new era for women in rowing, and one worth staying for.